Checked: 12-11-2023 by

Vicky Ryan Next Review: 11-11-2025

Overview

This guidance has been produced for primary care professionals in the Bristol, North Somerset & South Gloucester (BNSSG) area and is designed to complement existing clinical guidelines available to GPs via Remedy.

The aim of this guidance is to provide the ‘headline’ clinical assessment priorities for children presenting with the most common urgent care presentations. The guidance here is not exhaustive and clinicians should also familiarise themselves with full clinical guidelines for each condition.

The most common urgent care presentations are:

- Abdominal pain

- Asthma & wheeze

- Bronchiolitis

- Croup

- Fever & minor infections

- Gastroenteritis

- Head injury

Tips and Tripwires in Urgent Paediatric Primary Care - This publication from BrisDoc may help increase clinicians knowledge and confidence in managing urgent problems in children and young people. It has been endorsed by Paediatric Emergency Consultants from the Bristol Children’s Emergency Department and the Urgent Care Network of the GPCB © 2023.

|

Normal values for infants and children

|

|

Age

|

<6 months

|

6 months

|

1 year

|

2 years

|

5 years

|

|

Heart rate

|

110-180

|

120-160

|

100-150

|

95-140

|

80-120

|

|

Respiratory rate

|

30-60

|

30-50

|

20-40

|

20-30

|

20-25

|

Abdominal Pain

Key points:

- The key diagnostic distinction that needs to be made with acute abdominal pain is between surgical and non-surgical causes. When a surgical cause is considered likely the child should be discussed directly with the paediatric surgery team via the UHBW switchboard on 0117 9230000. If there is uncertainty, the case can be discussed with the Children’s Emergency Department (CED) team on 0117 3428666.

- Non-specific abdominal pain is very common but is a diagnosis of exclusion and this diagnosis should only be made once serious pathology has been considered.

- Symptoms in neonates and younger infants are often erroneously attributed to abdominal pain by parents. A thorough examination and consideration of a broad range of differential diagnoses is required in this age range.

- Repeated examination is useful to assess for the persistence or evolution of signs and response to treatment.

- Analgesia should be given and does not mask potentially serious causes of pain.

- Investigation should be guided by the clinical assessment – most children do not require further investigation.

- True bilious vomiting is dark green and warrants urgent surgical referral.

Common and time critical causes of abdominal pain in children:

|

Neonates

|

Infants and younger children

|

Adolescents

|

|

Hirschprung enterocolitis Incarcerated hernia

Intussusception

Necrotising enterocolitis

Volvulus

|

Abdominal trauma

Appendicitis

Constipation

Gastroenteritis

Incarcerated hernia

Intussusception

Meckel diverticulum

Mesenteric adenitis

Ovarian torsion

Pyloric stenosis

Testicular torsion

Volvulus

|

Appendicitis

Abdominal trauma

Cholecystitis/

Cholelithiasis

Constipation

Ectopic pregnancy

Gastroenteritis

Inflammatory bowel disease

Ovarian cyst – torsion/rupture

Pancreatitis

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Renal calculi

Testicular torsion

|

Non-abdominal causes of abdominal pain:

- DKA (including as a new presentation of diabetes)

- Migraine

- IgA Vasculitis (previously Henoch Schonlein Purpura)

- Hip pathology

- Pneumonia

- Psychological factors

- Sepsis

- Sexually transmitted infection

- Sickle cell disease

- Toxin exposure or overdose

- UTI/pyelonephritis

Click this link to access guidance about the assessment of chronic abdominal pain

Asthma & Wheeze

Key points:

- Acute wheeze can have a number of different causes including asthma, viral infections, pneumonia, inhaled foreign bodies, gastro-oesophageal reflux and cardiac failure.

- Acute wheeze with viral infections is very common in pre-school children and can be severe. These wheezing episodes are often different from those in older children with asthma. They are usually due to viral infections alone and they often respond differently (or not at all) to ß2 agonists. The evidence for the use of steroids in children with preschool wheeze is not robust and frequent courses have significant side effects. Steroids are unlikely to be beneficial in children <5 years if they have saturations >92% and only mild respiratory distress.

- Wheeze in infants (<12 months) is usually associated with bronchiolitis and should be managed accordingly.

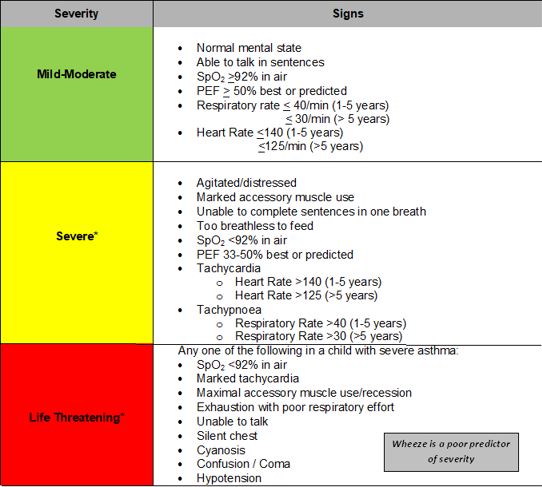

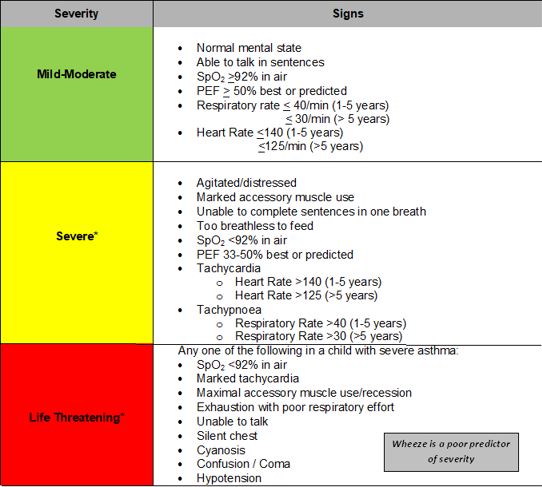

Assessment of acute wheeze/asthma:

*Children with severe or life-threatening wheeze/asthma should be treated with salbutamol nebulisers and prednisolone (if possible) whilst arranging emergency transfer to CED. Call the CED team on 0117 3428666 for guidance on acute management whilst awaiting an ambulance.

In children with mild-moderate wheeze/asthma give up to 10 puffs of Salbutamol by MDI + spacer & assess response (in < 5 years: 5-10 puffs, 1 puff per minute)

- If there is a good response to treatment:

- Discharge home with b2 agonist

- Consider 3 day course of once daily prednisolone (see notes on preschool wheeze above)

- Provide a written wheeze discharge plan

- If there is a poor response refer to CED on 0117 3428666

Click this link to access guidance about Asthma & wheeze

Bronchiolitis

Key points:

- Bronchiolitis is a clinical diagnosis usually made in infants less than 12 months. A characteristic history and examination includes cough and coryzal symptoms with widespread inspiratory crackles and expiratory wheeze.

- Mild bronchiolitis can usually be managed in the community. Clinical features of mild bronchiolitis are listed below. Infants with more severe features should be referred to CED (0117 3428666).

- Alert and normal behaviour

- Warm and well perfused with a CRT <2 secs and normal colour

- Moist mucus membranes and no signs of dehydration

- Respiratory rate <60 in infants <12 months (<40 in older children)

- Sats 94% or above

- None or mild chest recession with no nasal flaring or grunting

- Feeding >50% of normal

- A lower threshold for referral to CED is required in infants with the following:

- Pre-existing lung disease, congenital heart disease, neuromuscular weakness, immunocompromised

- Age <6 weeks (corrected)

- Prematurity

- Duration of illness <3 days

- Concern regarding parental inability to recognise deterioration

- There is no place for b2 agonists or steroids in the treatment of bronchiolitis

Click this link to access guidance about Bronchiolitis

Croup

Key points:

- Croup is a clinical syndrome resulting from upper airway inflammation. It is a clinical diagnosis characterised by a barking cough, inspiratory stridor and a hoarse voice. A moderate fever may be present. It is usually viral in cause (80% parainfluenza virus).

- The usual age range for croup is 6 months to 6 years with a peak incidence at 2 years of age.

- It is important to consider differential diagnoses such as:

- Foreign body inhalation

- Epiglottitis – rapid onset, toxic looking child with high temperatures and drooling

- Anaphylaxis

- Laryngomalacia

- Peritonsillar abscess (quinsy)

- Mild croup can be managed in the community. Symptoms of mild croup are listed below. Children with more severe features should be referred to CED (0117 3428666).

- Alert and normal behaviour

- Warm and well perfused with a CRT <2 secs and normal colour

- Respiratory rate <60 in infants <12 months (<40 in older children)

- No stridor when calm and occasional barking cough

- In mild croup consider a single dose of dexamethasone (0.15mg/kg). Not all pharmacies keep in stock. If likely to be a delay in issuing then give oral prednisolone 1-2mg/kg - a repeat dose may be required at 12 hours.

- Children with persistent stridor and/or subcostal or sternal recession should be referred to CED (0117 3428666). If possible administer a dose of dexamethasone (0.15mg/kg) or prednisolone (1-2mg/kg).

Click this link to access guidance about Croup

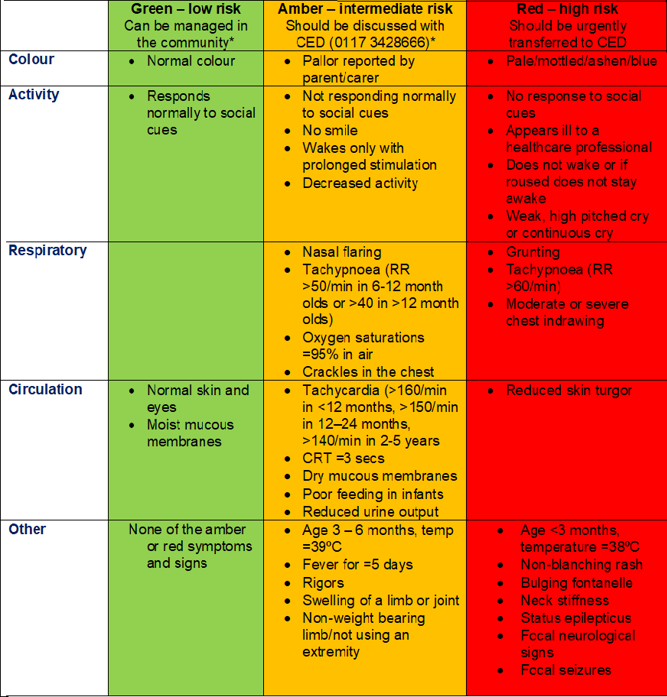

Fever & mild infections

Key points:

- In infants <4 weeks measure body temperature with an electronic thermometer in the axilla. An infra-red tympanic thermometer can be used in children >4 weeks.

- In infants under 3 months:

- Any fever of ≥38°C requires referral to CED (0117 3428666). The only exceptions are clinically well infants who have developed a temperature within 12 hours of vaccinations (not the rota virus vaccine).

- Take any parental report of fever seriously, even if not measured by a medical professional.

- When a child has been given antipyretics, do not rely on a decrease or lack of decrease in temperature to differentiate between serious and non-serious illness.

- Beware that classic signs of meningitis are often absent in infants with bacterial meningitis.

- Children with evidence of meningitis or sepsis should be treated with IM benzylpenicillin (300 mg). If there is clinical uncertainty discuss the case with CED (0117 342 8666).

- In children 3 months – 5 years:

- Take any parental report of fever seriously, even if not measured by a medical professional.

- Do not use a reduction in temperature after antipyretics to differentiate between serious and non- serious illness.

- Beware that classic signs of meningitis are often absent in infants with bacterial meningitis.

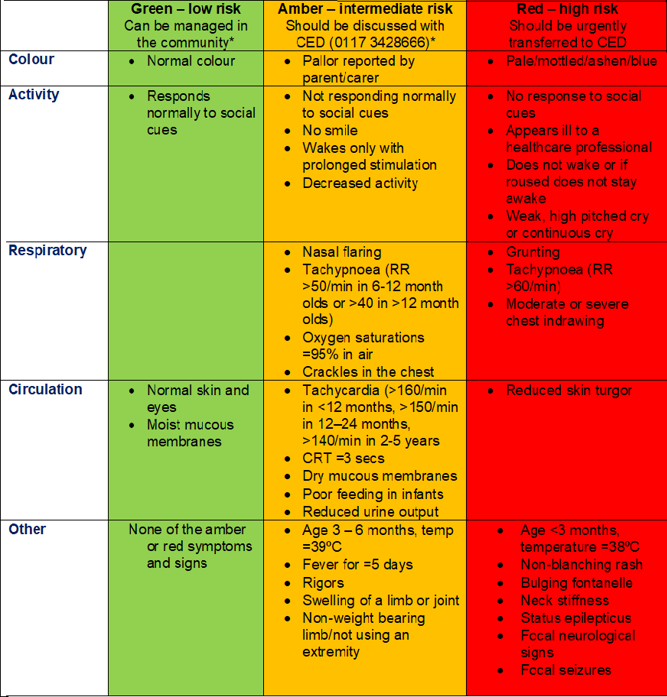

* Infants < 3 months old any fever of ≥38°C requires referral to CED (0117 3428666). The only exceptions are clinically well infants who have developed a temperature within 12 hours of vaccinations (not the rota virus vaccine).

Click this link to access ED guidance about fever in infants <3 months, fever in children 3 months to 5 years

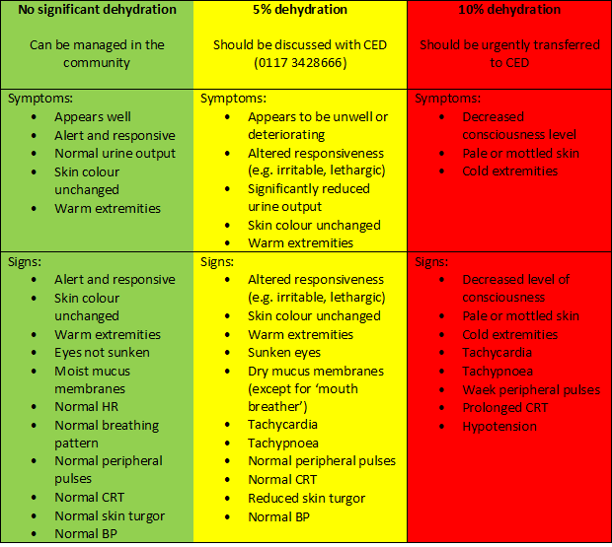

Gastroenteritis

Key points:

- Gastroenteritis is defined as diarrhoea +/- vomiting +/- abdominal pain.

- Children with just vomiting or pain without diarrhoea should be assessed for other causes before a diagnosis of gastroenteritis is made.

- There should be a lower threshold for discussing cases with CED (0117 3428666) if there are significant comorbidities.

- The following features should prompt careful consideration of alternative differential diagnoses:

- Severe abdominal pain or abdominal signs

- Persistent diarrhoea (>10 days)

- Blood in stool

- Bilious (green) vomit - should all be referred for assessment in CED (0117 3428666)

- Persistent vomiting without diarrhoea

- In most children with gastroenteritis no investigations are required. Faecal samples may be collected for bacterial culture if the child has significant associated abdominal pain or blood in the faeces, as a bacterial cause of gastroenteritis is more likely. However, these results usually don't alter treatment.

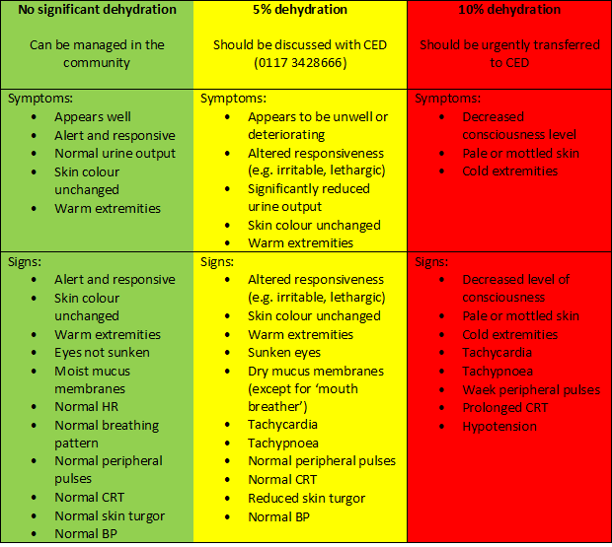

- Oral rehydration is the mainstay of gastroenteritis management either with oral rehydration solutions (e.g. dioralyte) or apple juice mixed 1:1 with water. Drinking small quantities frequently should be encouraged.

Click this link to access ED guidance about gastroenteritis

Head injury

Key points:

- Grading of head injuries

- Minimal head injury: low mechanism injury (e.g. ground level falls or walking/running into stationary objects), with no signs or symptoms of head injury other than scalp abrasions and lacerations. These can be managed in the community. A head injury information leaflet should be provided.

- Mild head injury: features include witnessed loss of consciousness, definite amnesia, witnessed disorientation/confusion, or vomiting in a patient with a Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 13-15. These should all be referred to CED for assessment (0117 3428666).

- Moderate head injury: features of intracranial injury, with GCS of 9-12 at any point. These all require emergency transfer to CED.

- Symptoms and signs of a potential intracranial injury include:

- GCS <15

- Drowsiness

- Lethargy

- Irritability

- Headache

- Vomiting

- Behavioural change

- Lateralising neurology (including false lateralising signs)

- All children with a bleeding tendency (congenital or acquired) should be referred to CED (0117 3428666) for assessment.

Click this link to access guidance about Childhood Head Injury Assessment And Management

Resources

A PDF version of the guidelines above is available: Common Childhood Presentations to Urgent Care_V3

Tips and Tripwires in Urgent Paediatric Primary Care - Increase your knowledge and confidence in managing urgent problems in children and young people.

Endorsed by Paediatric Emergency Consultants from the Bristol Children’s Emergency Department and the Urgent Care Network of the GPCB © 2023.

Efforts are made to ensure the accuracy and agreement of these guidelines, including any content uploaded, referred to or linked to from the system. However, BNSSG ICB cannot guarantee this. This guidance does not override the individual responsibility of healthcare professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient and/or guardian or carer, in accordance with the mental capacity act, and informed by the summary of product characteristics of any drugs they are considering. Practitioners are required to perform their duties in accordance with the law and their regulators and nothing in this guidance should be interpreted in a way that would be inconsistent with compliance with those duties.

Information provided through Remedy is continually updated so please be aware any printed copies may quickly become out of date.